The role of Ascension Church over the decades is reflected in its

motto “A Church in the community, for the community”. Built (and

rebuilt) as a philanthropic initiative by the Felsted School

Mission Association, the initial building, on the site of the

present-day church, opened in 1887. The congregation grew

substantially and, by 1891, the building could not accommodate it.

A new church was built that was dedicated on Ascension Day, 8th

May 1902. Information provided by the Church’s website indicates

that “in the late 18- and early 1900s it was delivering the kind

of community-based youth work that any church today would be proud

of, including a swimming club which taught the children living

near the notoriously dangerous docks to swim, and a football team,

while the thriving dock community ensured weekly attendances of

over 600 on a Sunday.” Nevertheless, like so many institutions in

the area, the church was affected by the social turbulence linked

to the closure of the Docks in the 1980s. Mass unemployment and

people leaving the area coincided with the need for substantial

repairs to the fabric of the building. Closure, however, was

averted and a new-look Ascension Church building was rededicated

in December 1995.

www.ascensioncc.org.uk/history

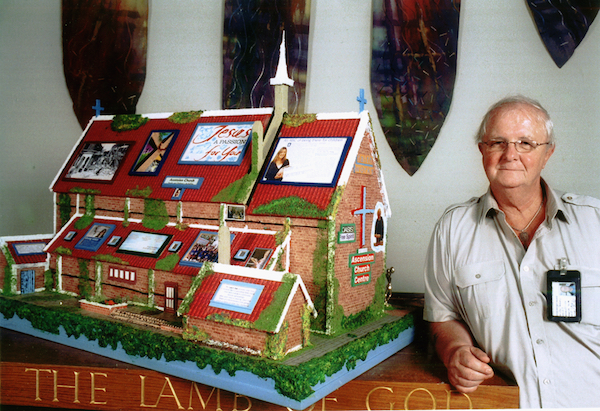

William: Yes, the model of the church was an exercise started at Felsted School in Essex which is a private school or public school though you can get in there with a bursary or by passing an exam. It's 400 years old, the school, and I've been there many times and they got the kids who were 11 to build a model of the Ascension church which the school had paid to have built at Custom House to teach the children to read and write. Basically it started out as a wooden shed and eventually they built the church and they always had a link with it, with the East End. The kids built this rough wooden church as an exercise to get 25% of their marks for their exam and I didn't see it for a long time but it was a rough church and left there. It was in a rough state but the kids had done the best they could with it. They did what they thought was right and I saw the vicar he told me about it and I remember it being unloaded off a van and I'd forgotten about it…

A school teacher came with some children from Felsted, the public school, to visit the church regularly and he said it should be in a case. So I said ‘I don't have a case. It needs polymer’. There was somewhere in Canning Town where I could buy polymer. He said ‘I'll leave £100 now, then can you start work on it right away? Can you buy the polymer and the board and make the case and a table for it? So the £100 more than covered it. So I put it on the table and made the glass or the polymer case for it and it's now used to teach the school children. It covers all the aspects of the Ascension church and the area. I went into it and put all the things that happened there. So I made small pictures or little plaques to put over it so everybody knows what happens there. So all the different classes in the church are on there if you look at it and it tells you where it originally came from.

“Down in the busy east of London where the steady rumble of heavy

vans laden with merchandise, the whirr and clang of cranes and the

rattle of winches resound always in the ears of the passer-by,

stand two large gates, which are the entrance to Mecca of the East

End labourer. For here are the docks, whose business, directly or

indirectly, gives employment to a great proportion of the lower

stratum of dwellers in the east” [Dickens, Dock life]. The Royal

Victoria Dock (RVD), originally known as the Victoria Dock, opened

in 1855. One and a quarter mile long, the dock was directly

connected to the railway system and hydraulic power was installed

from the start. It was the first dock built expressly for steam

ships.Such was the role of the Royal Victoria Dock in the import

of foreign grain that, in the first 5 years of the 20th century,

it saw the creation of three giant mills, representing the largest

milling installation in the British Empire. The largest of them,

Vernon & Sons’ Millennium Mills, was able to process 100 sacks per

hour. The Royal Albert Dock opened in 1880. Served by the Great

Eastern Railway, this was a dock equipped hydraulic cranes and

steam winches, capable of handling ships up to 12,000 tons. By

1886, there were in existence in the Port of London 7 enclosed

dock systems, leading to over-provision and, consequentially,

financial difficulties. At a time when technology was advancing

fast, the lack of investment in the port facilities risked making

them inefficient and obsolete. To counteract this situation, the

Port of London Authority (PLA) was created (following the Port of

London Act of 1908). To avert a financially catastrophic situation

for London, the PLA decided to take on a programme of

modernisation. Thus, the King George V Dock was built able to take

vessels of up to 30,000 tons. As regular passenger lines became a

lucrative business, the King George V Dock could berth the biggest

liners of the time. Together with the Royal Victoria and Royal

Albert Docks, when the King George V Dock opened in 1921, it

became part of the largest area of impounded water in the world. A

fourth dock was later planned for the Beckton area by the PLA but

abandoned in the mid 1960s. The Royal Docks achieved their peak in

the 1950s and early 60s, handling mostly deep sea cargo trades

from the British Commonwealth.

www.royaldocks.org.uk/history

Olga: How was it for you a young person working in the docks?

William: Well, I started off on the ships when I was 18 (1959) and I worked as a shore steward on the ships doing the stores. It was casual work, all that work was casual work, and I got on all right with that and I worked on the Royal Mail Lines and the Royal Mail lines had split things in two, there was the shore stewards and the shore crews and I was on the shore stewards and they didn't pay a lot or have a lot of overtime. They was very easy-going, you could sometimes have a couple of easy days in the mess room playing cards with nothing to do, so after 2 years of that I transferred over to the Marine riggers of the Royal Mail which took the place of deep sea crew. Most of the men had already been away at sea. They did all the rigging of the ships when it was in the dock and the moving of the ship. All of that was done by them and I did that and the moving of the ship and the tugs come and you would move the ship with the tug. You would go to stations and move it and then you would tie it up at another birth and you also maintained all the running gear on board, the derricks, which they don’t have any more and all the wiring and all the splicing and the life-boats had to be serviced and everything that the deep-sea crew did, you did, you had to learn it but some of the men knew it because they’d been away from the age of 14 and had been in the second world war and some of their stories were horrific. I put my name down to become a stevedore and I decided it was the thing to do and I’d got to know about it through a friend of a friend who had known me since I was a baby and I worked as a marine rigger up until 1966, no I tell a lie, 1965, and then I got a letter to say I'd been nominated to go to the Dock School for 3 weeks and a 2 week training. Well I had the advantage that I already had training so I was sent to the Dock School in the East India Dock (which is no longer there) and then you passed an exam at the end of it. You did general derrick work and it was to show that you had, that you were able to do derrick work as well as driving - well, I’d already driven winches, so I knew how that worked and at the end of, I think it was 3 weeks they gave you papers for your exam. It wasn't really an exam as it was all done in boxes but if you passed that they give you a book that you could go and work on the Monday for the call which was the men lined up on the pavement every morning, not on the road, but on the pavement. You have to imagine the Docks. They stretched for miles. And you lined up and in the road would be gangers and ship workers (they were called ship workers, the other men) and they would ask for so many men and you would hand your book out and not many would take you as they had regular gangs who stayed together but they were still casual and we had a pool, a national labour pool , it was the same all over the country and if there was no work at all you had to go there and you got money, I think it was 9 pounds 5 shillings less tax and insurance if you dabbed on for 5 days. I never had a full week of dabbing on. Never.

Olga: I was thinking, if you had an uncle or a dad doing the job then that would help?

William: Yes, some of the time it did. But a mate of mine, his father had a gang and he had two sons and the first day he wouldn't pick his sons up. They had to go home. And his mum said to him, said to her husband, ‘Our two my boys were on the stones. Why didn't you pick them up? And he said “No they've got to learn to find the work themselves.

Olga: You said something before about when the machines and forklifts came and when people said, ‘this is the end’.

William:Yes, containerisation.

Olga: Tell me about that.

William: The containerisation started in 1943. The Americans in the war used containers. On one occasion they had planes in them on a ship, on a ship’s deck. They put the planes in containers. This time people in high places did take notice about what happened, what has been done, and so in 1952 the shipowners, they got one man who was the governor of Shaw Saville line as merchant marine and he studied the unloading and loading of cargo on ships across all the shipping lines in the world. But the company got together and he was the best one. He spent 2 years travelling the world at their expense all the ports to make a report on the way the men worked all over the world. Anyway that was 1952, but the initiative was from the American containers. It was an American idea but the British pulled the men out when the first containers came here. They were small ones and the men were blind to what was happening and they were lifted up, put on the quay and the men just unloaded them on the quay, so the men thought, ‘We've got no fear of this’ and I thought, ‘they won't be like this all the time’. ‘No we wouldn't let that happen, we wouldn't let containerisation happen’ but the years rolled by and he came back with his report and told us about containerisation. He come back and I read his report. It’s a book. Obviously, a place like Russia or China wouldn’t be interested because there such a surplus of labour and they done what they was told. And for you in Portugal, Salazar in Portugal. He weren't interested as they could call up slave labour whenever they wanted to and they certainly didn't want to put any money in. So they wanted to carry on as they was. We knew that things wouldn't carry on as they were. Anyway the crunch of the report was that for 500 years cargo been lifted 30 feet. It went up 30 feet and it went down 30 feet for a minimum of 500 years. But there had to be another way and the container was it. So they said that they had to build new ships called cellular ships. So the Americans first built the new ships called Lancer ships. They was part container and part general cargo and after some years of haggling around the world they realised that the old job of being a docker wasn't an attractive one. Some of them, like in Jamaica and in Africa were working for peanuts like slaves so it was really only on the industrial side of the planet like for example Australia, New Zealand and Canada was against it. Of course they had strong unions and America had the teamsters union with Hoffer. He was taken to see one of these new ships and asked what he thought of it. And he said, ‘Fuckin sink it. We can’t have that.’ we thought, ‘What! We can't have that. You could see thousands of job would have to go. That's the demise of the working bloke’ and we said, ‘We can't agree with that.’ You could see there was a lot of jobs that were going to go.

Faraday secondary school, Canning Town. Holborn Road council

school, planned by the school board, was opened in 1904 for 1,600.

The building was of the standard three-storey type, but hipped

roofs and dormer-windows were substituted for the usual gables. It

was reorganized in 1933 for senior boys, senior girls, and

infants, and in 1945 as a mixed secondary modern school. From 1949

it was called Faraday, a name which had been used in the 1920s for

the day-continuation institute occupying part of the Holborn Road

premises. The building has now been demolished to make way for a

housing estate. More information can be obtained from ex-alumni.

Brampton Manor is an outstanding 11-18 Academy (2012, 2018),

located in East Ham, London. In April 2011, the school chose to

convert to Academy status, becoming the first school in Newham to

do so. It is a multi-academy trust and a national support school,

working very closely with Langdon Academy. The facilities include

a 300-seat theatre, drama and dance studios, recording studios, a

TV studio, fitness suite, floodlit Astroturf, climbing wall,

tennis courts, playing field, sports hall, gymnasium and a farm

(Brampton Manor school website, 2019). In 2019, the school

celebrated sending 41 of its students, the majority of whom were

of minority ethnic backgrounds, to study at the universities of

Oxford and Cambridge that year (Weale, 2019).

Faraday Secondary Modern

School Facebook Page

Eve: So by the time you left school you had already learnt a lot of very useful skills that you were able to use in life?

William: Yes, I could put a plug top on, change light bulbs or wire a light up. You were taught how to do that. You were taught on an old electric iron. It was taken to pieces and the boys were shown how the elements worked in an old electric iron - which is still basically the same as today, how it worked. You were taught how to cut sheet metal out. You had a big saw for cutting steel bars, not all the boys were allowed to use these, but once I passed the tests I was allowed to use them on my own. In fact, I used to make things to help the teacher as he had work to do. He used to give them to me to drill and tap through. I made an aquarium. I made toasting forks which were common in those days to toast bread on a coal fire. I used to make all sorts of things. I used to make trays which were popular then out of copper ...

Eve: So have those skills stood you in good stead, have you used some of those in later life?

William: I've used all of them.

Eve: Academically it's doing very well isn't it?

Jason: Yes, they call it the Eton of the East End because it sends as many people to Oxbridge as Eton does.

Eve: Really, that's fantastic.

Jason: As at the higher end of the private schools

Eve: Amazing

Jason It wasn't that good when I was there.

Eve: What do you think that might be due to?

Jason: I’ve heard it was due to the headteacher who came in when my niece was there and I’d left years before. He was very strict and clearly for some reason it was a benefit and paid off. It was very strict and very disciplined and very rigid but that's worked for that reason.

Eve: If you had to choose, I know you don't have children yet, but if you had to choose a school for your child what qualities do you think you would choose?

Jason: I would look for academic outcomes, how many people got As to Cs and how many they sent to Oxbridge, they would be my main or at least my first consideration. Definitely. And then I would look at the facilities themselves how well the school looks kept, and yes, and how many different facilities are available, sports facilities and things like that, how much money has been put into the building itself.

The Sri Murugan Temple in East Ham has been described as a haven

of spirituality and is a tribute to the multiculturality of the

area. The Temple is a large and impressive edifice, built of white

stone and marble all of which were brought across from India. Its

entrance, underneath an ornate 52 foot tower, reveals polished

granite tiles from India and reflect the light carefully designed

to fall delicately around the deities adorned with glowing lamps,

fruits and flowers (The Shady Old Lady, 2019). The Temple’s

journey began humbly in 1975 in a terraced home in London. The

congregation of Tamil-speaking Hindu community raised the £3.5

million to build the Temple on the site acquired in Church Road 22

years ago, which opened in 2005. The Temple reflects what Gregory

et al (2013) describe as a delicate syncretism in its combination

of cultures from east and west, of traditional and modern, merging

with its surroundings in a road that previously housed a Church.

The same note was achieved in its design and construction as the

building follows a symbolic design drawn by Indian architect Sri

Muthiah Sthapathi and chief priest, Sri Naganathsivam Kurukkal in

accordance with Hindu Temple principles, in collaboration with

British architect Terry Freeman and a team of Indian experts to

build this traditional Indian building according to British

planning law.

www.londonsrimurugan.org

Eve: Did you go to the big temple, the Lord Murugan Temple in East Ham?

Brian: Yes I've been there couple of times. I used to go to the big temple in Neasden which is a Gujarati one. If you go to the one in Neasden in my opinion it's even better than The Lord Murugan Temple and they've got a lot of things you can watch. I was very interested in Hinduism growing up. I used to go to the temple in Neasden quite a lot.

Eve: Your parents weren't religious, were they?

Brian: No, they weren't. I had an interest in Islam for a while and then I had an interest in Eastern religions, in Hinduism. I've actually studied Hindi. I studied Hindi for two years during my undergrad work. I don't know how much influence that was, being in the area that I was in. Some people thought it might be. But I don't know how much of an interest I got because of that.

Eve: What was your thesis about?

Brian: My MA dissertation was a completely different topic. My undergraduate dissertation was on the representation of Hasidic Jews in the media which had a bearing on the area which I am in. With religion, when I was growing up, maybe because I was living in a multicultural area and you had a source of exposure maybe you're forced to think about religion, coming from English people and generally not being very religious, but I noticed that religion was a very important part of people's identity when I was growing up and the Muslim community being very strong in their identity and other communities were very strong in their identity in comparison with those of us with no religion perhaps more so than the other side of being a migrant maybe that's where it all comes from that interest.

Working Men’s Clubs appeared in the 19th century to provide recreation in industrialised areas for men and their families and were at their highest number in the 1970s. Most of the existing ones are still associated to The Club and Institute Union (CIU), an organisation formed in 1862 by members of the aristocracy and high-ranking politicians to help provide working men with “a place to go for ‘sober social discourse’ after work, where they could meet friends, relax, perhaps play some games, read newspapers and books”. Clubs were to be an alternative place of leisure to the public house where many working men spent their free time and usually their wages. The CIU assisted in setting up clubs to private members (rules and regulations, accounting), offering advice and sometimes financial assistance as well as patronage. The clubs quickly started to sell alcohol and the members decided to run the clubs by themselves (Cherrington, 2012). Run by a committee, only members and their guests could attend the clubs. Despite their name, women were also allowed to attend. Nevertheless, women only achieve full parity of rights in 2007. The East Ham Working Men’s Club closed its doors in May 2019, after 130 years serving its members (Whetstone, 2019).

William:I was President of the Working Man’s Club. It was always just men, but then, in the 1980s the women wanted to set up a creche which we did, with toys. As we thought, some of the parents used it as a dumping ground for their children whilst they went off to have a drink. At that time, women were only associated members in their husband’s name, not on the committee. But it was legally their right to become full members, to sit on the committee and to vote, as long as they paid. The men had a meeting to discuss the right of the women to sit on the committee as equals. Some men disagreed and refused to continue on the committee. They just left the room. But it was decided to fulfil the equality rues and allow women the right to stand for the committee. Now it was customary at the AGM for those wanting to stand to stand up on the chair. I warned them about this and that they should know about it for the way they dressed. But to my amazement, they all came wearing mini-skirts! They got up on the chairs and said ‘That all right boys?’ Anyway, 3 were elected. The elected manager was also a woman…. When the women ran the club, its income went up by 30% with the first one and then by 50% with the second. We decided to give her a bonus but that upset the wife of one of the men that had run it.

‘The Burnell Arms pub has been recently replaced by the Lakshmi Temple opposite East Ham underground station’

Jellied eels or in pies with mash and liquor, cockles and winkles are as part of the East End as Cockney and pubs. Since the 18th century, eels, abundant in the polluted Thames were the easy food for poor people, sold in the streets before being brought indoors for pie and mash shops in the late 19th century. At their height, pie and mash shops were as popular as fried chicken or burgers are today. European eels and flounders were the first species to recolonise the Thames Estuary after being considered "biologically dead" in the 1960s. Nowadays, most eels used in Pie and Mash shops come from Holland or Northern Ireland as the eel population in the Thames fell from 1,500 in 2005 to just 50 in 2010. (BBC, 2010). Together with jellied eels, cockles and winkles were common nibbles in pubs. Pub life was an important part of social life in the East End. As in the rest of the UK, where 1 in 5 pubs between 2008 and 2015 were converted into residential properties, pubs in the East End also closed. In London, 1,300 pubs closed in the decade to 2013 (Crerar & Reinwald, 2013). In addition to different forms of keeping in touch with friends, some people suggest that the struggling economy, higher rents, land prices, smoking ban, tighter regulations and competition from supermarkets have all played their part (Boyd-Wallis, 2015), while others blame the pub industry’s restrictive practices for the pubs demise (O'Sullivan, 2013).

The development of the East Ham Levels started with the construction, between 1864 and 1875, of the Northern Outfall Sewer, a colossal drainage system for the London metropolitan area. Conceived by Joseph Bazalgette, the sewage treatment works served all the combined sewage of London north of the Thames and were the largest sewage treatment works in Europe. They contributed to alleviate pollution and ill-health in the city, ending cholera and leading to the development of the flushing toilet. Bazalgette’s expertise is still functioning as planned, over 150 years later, and the network he conceived forms the backbone of London’s sewerage system.

Michael: Mainly just playing out. We used to play a lot on what they call The Greenway now, round the back there, we called it the Sewer Bank. We used to play a lot up and down there, getting in to … we used to get into… they’ve got concrete boxes over there which is a vBent outlet for the sewers and we used to get in there a lot and mess about.. now we know it would be dangerous cos there were fumes and stuff, but we didn’t have a clue, but yeah it was mainly around sport and that, not so much building

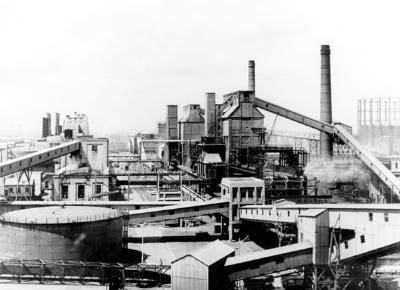

Initially, the area where the Gas Works were situated, conveniently close to the docks, was far enough from the city’s residential areas to avoid concerns regarding the toxic residues from the gas production process. The ash and waste from the Beckton Works were piled in the open marshland around the factory. The large number of rubbish mountains was given by locals the enduring nickname of “Beckton Alps”. The one remaining “Alp” has, over time, been used as dry ski slope, a film setting and, nowadays, a site of local scientific and wildlife interest as well as providing a view point over the London and the Thames Estuary. (Willey, 2006).

William: It’s listed now. It was to be demolished, but they made a lot of films there. But then it was listed, which it wasn’t meant to be. They couldn’t pull it down. It’s a Nature Reserve as well. So the animals live in it so they had to leave it. They built on a lot of the land, but the works itself over the back there became a Nature Reserve, then film companies rented it out and one of the films made there by Stanley Kubrick was famous. ‘Full Metal Jacket’ was made there on the story of the Vietnam War, so with a few alterations and they started using it as a film set

Eve: What was it like when you were young?

Eve: Well, a pile of smoke was over it here all the time, all over the houses as the retort ovens turned the coal into coke and coal gas and at night it used to glow red in the sky all the time and that great big heap up there with the trees on that used to be a tip of ash and it had every chemical known to man in it.

Eve: It was called the slag heap wasn’t it?

William: Slag heap, yeah. It had a railway going up to it and they dumped all the stuff on it and it was left for years, and then they were thinking of clearing it, but the cost of clearing it, well, where to put it? It was highly toxic. It had a moat around it and nothing could live in it in the water because it was highly poisonous, and then they come up with an idea. They could landscape it. It took two years to cover it and put earth on it. Well, they put sand first and then a plastic sheet on it before they put trees up there and then they put a walkway. There’s a walkway going right up to the top now. There’s like a forest they made. They had students there planting trees. One day, they had hundreds of them planting trees. There’s a walkway right up to the top now. But it took 2 years to make it possible. And they found unexploded bombs, they found a steam engine buried there and no-one knew how a steam engine could be buried there or why it was buried. They took it out and cleaned it up and took it to a museum. I think they took it to a museum in York which had been part of the Gas, Light and Coke Company. At one time, they made it into a dry ski run. Two men came to Beckton. That was a success to start with and then they put a restaurant there. That’s a bad’un, but it’s still a walkway, a steep walkway to the top. And from the top you can look out over East London and to the west end on a clear day.

Eve: It used to dominate the whole area.

William: Yeah, it does now. But, it was, well, the smell coming from it, the smell coming from it was from the coal gas. You could smell the coal gas in the air. The man who owned this house originally, Alf, he was a foreman painter. He worked with the coal gas in the works

William: There were terrible illnesses caught there (Gas Works) but they never paid any compensation. One of the sisters of my mother, her husband died of an infectious disease caught in the gas works when he was working there but he never got paid anything for it. It was the Gas Works Union under Ben Tillett who formed that Union and Ben Tillett was a famous man and he formed the Union and organized the men inside the coke company and it gradually spread out. Ben Tillett, he was a famous man and he put together the Gas Workers’ Union to start with before it spread to other things. Before that, they had no representation. There was no representation for their health. If a man died they replaced him. That was it.

Described by Charles Dickens (1880) as “the largest distillery of gas-tar in the world, covering seventeen acres, and which does the creosoting of railway-sleepers, turning out some thirty thousand a week”, the site occupied by the Gas, Light and Coke Company was named after its governor, Simon Adams Beck, and became known as Beckton. Opened in 1870, Beckton supplied gas to over four million Londoners, as well as manufacturing by-products such as creosote, fertilisers, inks and dyes. It was not until the switch to natural gas in 1969 that the works were scaled down. (Willey, 2006).

During the Second World War, the marshland neighbouring the Gas Works, formerly occupied by hundreds of garden allotments, was used as a site for a prisoner of war camp.

William: After the war, 20,000 German prisoners stayed on voluntarily here to work. They didn't want to go back to Germany. Where I lived there was an Italian prisoner of war camp near the A13, the main Trunk Road, and they had better food than us. They used to come out of the camp with guards from the lorries and do building repair work on bomb damage and some of them spoke English and they had things that you could only dream of. They had sweets and things that we couldn't get and they lived in Nissan huts near the A13 and eventually they were asked if they wanted to go back and what I learnt later on was that every six months you were asked if you wanted to be repatriated and if you said no you stayed another 6 months and later that was done away with. It was very much an open society then. It used to make you laugh. When they got off the back of a lorry at night one of our soldiers would hand his gun to one of them whilst he climbed on the back of the lorry. You couldn't imagine that happening now. And the Americans who came here had ample food and that's how I learnt about chewing gum. They gave it to us. There was a station near here.

Amongst the most important factories in Silvertown, were those belonging to Henry Tate & Sons (1877) and Abram Lyle & Sons (1881), whose companies merged in 1921 to form Tate & Lyle, one of the major employers in the area outside of the docks. The newly formed Tate & Lyle maintained both refineries, Tate’s in Silvertown and Lyle’s in Plaistow Wharf, this latter only closing down in the late 1960’s. This decision contributed to the residential growth in these and adjacent areas. Tate & Lyle is a well-known national company which still operates locally at the Silvertown Refinery. The importance of these companies and the social role they played extended beyond the walls of the factory as they provided social programmes and initiatives that continued to be implemented after the merger. In addition to building a social club (the Tate Institute, Silvertown, 1887), Henry Tate was responsible for financing the Tate Gallery in Central London. The Lyles maintained the Margaret Lyle Maternity Wing at the then existing Queen Mary's Hospital as well as Lyle Park, a local riverside facility accessed from Bradfield Road. Tate & Lyle also offered a 6th form scholarship scheme to help the children of poorer families. With the advent of WWII, Tate & Lyle became a focus for female workforce given that, due to war recruitment, women took up the jobs left by the men, doing physically demanding jobs and attaining high status positions. Nowadays, the company employs a much-reduced workforce, as the ‘Sugar Girls’ were replaced by machines. (Barrett & Calvi, 2012; Royal Docks Trust, 1995)

William: When I first went to work, I worked in Tate and Lyle's for 2 years on the refinery.

Eve: What do you think you learnt there?

William: How to work machinery, different types of machinery you were trained to use. The bigger the machine and the more complex the job was you got men's wages for it so you got a man's wage for doing a man's job like working a really complex machine. I learnt a lot there as you used big machines which they taught you. One machine was a wringer and mangle. It was like a huge washing machine with sacks where the sugar was washed out and it used to go through this washing machine which was 40 foot long at least. At the other end was a huge mangle and a boy could work that. You didn't get extra money for that and you'd be standing at the back where the bags go through the mangle and that was difficult because it would be going round and round the rollers or you'd have to get up and reverse it and release the springs to get the sacks out and then it would go down the chute to a drying machine. You were doing that sort of work.

Eve: Do you think those sorts of skills are still learnt?

William: No, the jobs don't even exist. No, then we were loading a thousand tons in the silo. You were shovelling it in and putting it on the conveyor belt. You got a man's wages for that and you had to keep shovelling it one after the other and I used to work 6 to 2, 2 to 10 or 10 to 6 shifts. You got an half hour break but no matter where you was in the refinery you had to run to the canteen, eat your meal and run back ‘cos you was stopped money so all that had to be fitted into that time because they paid for the half hour. If you did the day work you didn't get paid for the half hour because the day work was considered to be 8 till 5. If you did a 13 hour shift on a Saturday and Sunday you got 2 half hour breaks and you worked 12 hours. And I mean work. It was piece work. I worked piece work all my time whilst I was there and you’d be running with sack barrows 3 hundredweight of cube sugar and you’d do that for 12 hours. Everybody smoked them days but they worked hard, they did work hard.

Christopher: I got a job there (Tate and Lyles’) so, since seventeen till now that’s where I’ve been basically I suppose, spent most of my time there.

Eve: What do you do there?

Christopher: It’s not very nice but insulation, so it’s quite itchy, so that’s basically it. It’s also metalwork as well, so we design and make metal as well. That’s the most difficult bit, but other than that, it’s pretty itchy.

Eve: I can imagine. And do you like the company you work for?

Christopher: erm.. For a while I enjoyed it… probably not so much now … even though I’ve been there for a while, it’s got samey samey… I enjoyed it at first but… whether I’ll change I don’t know. I’m not sure whether I’ll change I don’t know whether I’ll stay there or not but… it might change... I might start enjoying it again, you don’t know.

Eve: Yes. Do they provide any opportunities to sort of…do different…?

Christopher: Well, funnily enough, I’m just a contractor so I don’t actually work for Tate and Lyle themselves, but there’s always job offers, they’ve always got job offers to actually work for Tate and Lyle, so I could take one of those opportunities really.

The Mayflower Family Centre (1894) was the initiative of the Malvern College Mission. Originally called West Ham’s Dockland Settlement No. 1, like many other philanthropic institutions in the area, it appeared after the creation of the school board in 1871, to deal with the pressing needs of the population. Apart from health services, poverty and the lack of facilities for recreation and adult education were also urgent problems. It flourished under the wing of Sir Reginald Kennedy-Cox who invested his own time and money in the mission, secured royal patronage and raised funding through various means. Between 1924-29, he managed to build new club rooms, gymnasium, dance hall, theatre and a swimming-bath. Most activities ceased during WWII and, by 1957, the Centre’s existence was in peril. It was under the wardenship of Revd. David Sheppard that it became the Mayflower family centre, managed by a non-denominational committee, providing facilities for people of all ages but specialising in youth work and running a nursery school. (Powell, 1973).

Susan: It’s just off the A13 as you’re going towards Canning Town… but then it used to be called the Mayflower Family Centre and we used to go to church there on a Sunday, but then we used to… children could go there …they used to have children’s clubs…certain ages, I think some were 5 to 11 and then 11 onwards. But that was a fantastic place because…. You used to pay to go in I don’t know how much a penny or something …silly money but then you had the complete run and it was very very old. It even had a swimming pool in there. But you had the run of it. You could go up, go down you could go everywhere not the church… but the little ones… the hidey holes this place used to have. It was fantastic but they used to have people used to live there… but when I was growing up, the vicar there was a gentleman called

David Shepherd, but he was also a cricketer. He used to play cricket for England, and then he was a vicar. Then eventually, when I had my daughter in 68, she was the last person there he christened because then he became Bishop of Liverpool and he was there I think 68, 69. But it used to be a fun place because they’d take you out on days out and you ‘d go off to places like Herne Bay in a coach and all these sort of things you ‘d never do with your parents but you were in a coach. They took you to places and you grew up knowing if you went to the Mayflower and they had a trip you went on it. You went to the church Sunday night and I used to go to Sunday school there before we left the Mayflower, but everybody went to Sunday school and you’d get the Boys Brigade used to play their band through the street on a Sunday morning. You get the Sally Army used to do their band on a Sunday morning. It was something you knew would happen

Eve: Part of the routine of life.

Susan: Yeah. Because the bands used to come through and if your mum said you’d been good you could follow the band to the church and they’d meet you there and they’d have like the children’s church and you’d go off and do drawings and that and then you’d have the grown ups in the proper church you couldn’t go into until you were old enough not to make noises.

The London Docks were an obvious target for the air raids during WWII. London was attacked 71 times and bombed by the Luftwaffe for 57 consecutive nights. More than one million London houses were destroyed or damaged. It started on September 7th, 1940, a day that came to be known as “Black Saturday”. One of the first casualties, the Abbey Road depot in Bridge Road, Newham suffered a direct hit and collapsed killing workers and some of the firemen who came to rescue them. Although people were advised to keep shelters in their own backyards, deeply-buried shelters provided the most protection against a direct hit. In the early hours of Tuesday morning, 10 September, South Hallsville School in West Ham, where 600 people had taken refuge, was hit. Most of the 200 casualties were children (Calder, 2017). By the second week of heavy bombing the government ordered the tube stations to be opened. Each day orderly lines of people queued until 4 pm when they were allowed into the stations. By mid-September, about 150,000 a night slept in the Underground (Prigg, 2012). From 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941, 1,240 high explosive bombs and 67 parachute mines were recorded to have been dropped in Newham (Bomb Sight Project). By the end of the war, in West Ham and the neighbouring borough of East Ham, nearly three thousand people had been killed. Sixteen thousand homes had been destroyed and thousands more damaged (Hollow, undated).

James: It was a tough area to live in.

Eve: You were a child round here too… during the war.

James: Yeah, yeah, I was brought up….

James: No I come from .... Yes, so when the war started, we got evacuated to Blackpool. We lived in Blackpool till I was eight. Then I come here to live. All the family come back to their old house where they used to be.

Mary: Yes but you was here when the bombs was here.

James: Oh yes when the bombing was all on and we used to go on …. and when the doodlebugs hit, we used to go round the doodle bugs to find all what was there and all the rest of it.

Eve: Can you remember how you felt when you we there during the war were you scared?

Mary: I think when you’re kids you don’t

James: Not actually …. scared, you listened for the air-raid… siren and once it come we all used to go straight in underneath the stairs on the toilet and hide because the doodle bugs, you’d hear them coming. There was three dropped in Freemasons Road, where the Dog used to be, one was there. Mum was up the road here and then there was one down the bottom … the one in Freemasons Road where the store is now where the pub is … we was on that going over it when another lot of doodle bugs come and we all run and one of the boys …, he stood there and looked for more stuff and he got killed.

Eve: Do you think your children and grandchildren have any idea about what people went through here during the war?

Susan: No because my parents never spoke about it. I mean my mum worked in Tates’s during the war and the odd occasion she’d tell you about the doodle bombs coming over and she said when you used to leave early when you was on 2 to 10 shift, walking through, she said all of the sudden you’d hear it cut out and you’d think, ‘ Where’s that going to land?’ Where they was by the docks obviously they got bombed nightly and they just used to hide under the table and under the stairs.

Susan: When we used to go to school we used to go past a police station and it took a direct hit and the policemen were in the building and they all died, but you just see it as a bombed building. The school I went to took a hit and my dad was home. He was in the RAF and he was home and my grandparents, my school was here and my grandparents lived in this next road and everybody went to the school you know to get rid of the wreckage to try and save children. I mean children died and adults but that’s it. There’s no memorial, there’s no… it just happened. You cleared it away … everyone was shocked, and cos you had no papers and things… there was no local papers… I’m not saying no one cared but no one knew…. You just got on with it …London got bombed… the docks got bombed but they never actually picked out streets that got bombed…along with all the docks. The docks got bombed

Ham, from Old English 'hamm' meaning 'a dry area of land between rivers or marshland', appears in an Anglo-Saxon charter of 958 and then in the 1086 Domesday Book, referring the location of the settlement within boundaries formed by the rivers Lea, Thames and Roding and their marshes (information from Wikipedia). Traditionally a part of Essex county, East and West Ham were formed when the territory was sub-divided in the 12th century, remaining as separate administrative units until 1965 when they became part of the London Borough of Newham. After the Metropolitan Building Act of 1844, which restricted dangerous and toxic industries in London perimeter up to the river Lea, the contiguous area of West Ham became the chosen site for such industries. Population increased exponentially, as workers tended to live near their place of work and their slum living conditions became a cause of concern. By 1901, most of West Ham had been built up. By 1911, with 289,030 inhabitants, West Ham was seventh in size among English county boroughs (Powell, 1973) and the highest in 1921 with a population of 300,860. During WWII, over a quarter of the houses in the borough were destroyed, especially in the southern part, where the poorest buildings had been, leading the council to carry out redevelopment schemes between 1945 and 1965, replacing the bombed buildings with higher density post-war social housing. This contrasts with East Ham where housing consists principally of Victorian and Edwardian terraced town houses. Both areas are characterised by low income population. East Ham is a multi-cultural area, where most residents are of South Asia, African, Caribbean or eastern Europe origin. As of 2010, East Ham had the fourth highest level of unemployment in Britain, with 16.5 percent of its residents registered unemployed. Around 7 in 10 children living in East Ham were from low income families, making it one of the worst areas in the country for child poverty (information from Wikipedia). In 1998, West Ham was identified as one of the most deprived areas in the country and formed with Plaistow a regeneration area as part of the New Deal for Communities programme. Newham is undergoing a rapid transformation with some of the largest regeneration schemes in the country and is one of the most diverse places in the country, with more than 200 dialects spoken.

Michael: And I know when my family moved into this place, the rest of the family they just couldn’t believe it. They thought they were moving somewhere posh cos they was moving to East Ham. They couldn’t believe it really.

Debbie: Yeah, my aunt, my mum’s sister she… when we got married, she went ‘Oh are they buying a place then?’ My mum said ‘Oh no they‘ve got a place in East Ham.’ She went ‘Oh she’s going up in the world.’ Yes it was classed as being such a posh place.